How Virtual Reality Could Be the Future of Photojournalism

![]()

At first, if it weren’t for the contraption that makes you look half-alien, half-astronaut, The Enemy, a virtual reality experience on show at the Tribeca Film Festival, would be akin to most exhibitions.

“Fundamentally, as journalists, we’ve always been trying to arouse empathy so that viewers will care for a situation happening miles from their home or to others,”

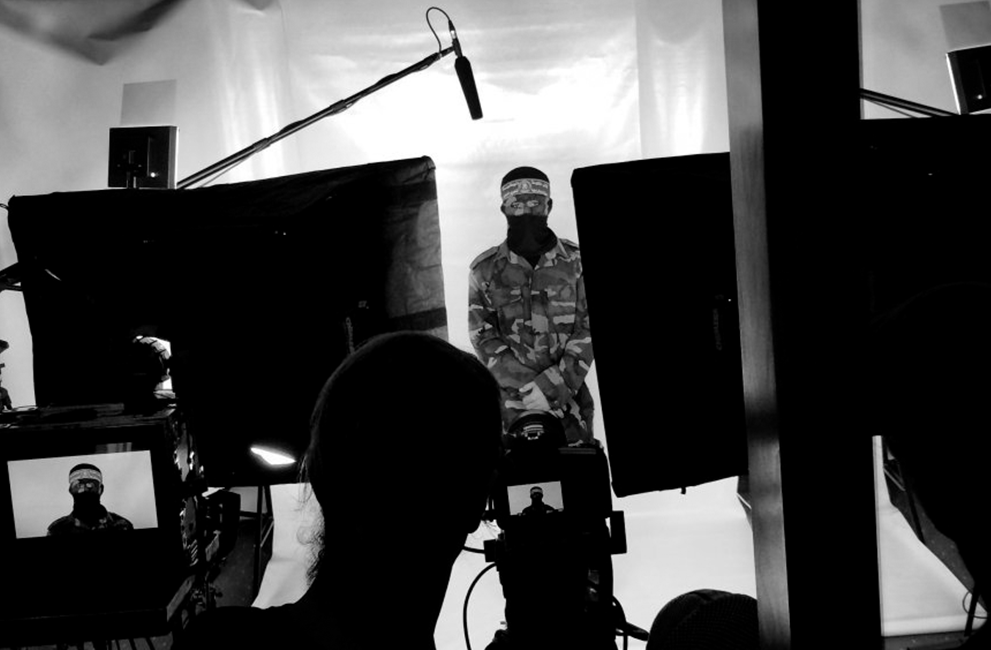

As you don the awkward oculus rift goggles and the backpack with the umbilical cord that ties you to the operating system, photos taken in the Palestinian Territories appear on opposing sides. As you would when touring a gallery, you approach either wall, focusing your attention on the scene depicted on the first image before moving on to the next. After a few moments, portraits of two adversaries, Abu Khaled, a garrison leader for the Democratic Front for the Liberation of Palestine, and Gilad, an IDF soldier, replace the depictions of everyday struggles. The two men don’t stay inanimate for long. At once, they take shape right in front of you, as sophisticated holograms answering questions about violence and peace.

The virtual conversation mirrors the interactions of an actual one. Come in too close to the simulated fighter, and they’ll draw back. Shift left or right and their gaze will follow you. Take a few step back and the volume of their voice weakens. After a few minutes, once the conversation is over, they fade away, leaving you alone in an empty room. At this point, removing the high-tech gear feels like waking up from an exceptionally vivid dream: you keep a distinct memory of the experience, yet are acutely aware that it was not real.

“I wanted to know what would happen if we took the likeness of the combatants I’ve photographed off the wall and breathed life into them,” says Karim Ben Khelifa, the mastermind behind The Enemy, which received funding and support from the Tribeca Film Institute’s New Media Fund. “How would people react? How would the public engage with them? And what impact would it have on their understanding or on how much they care?”

For the better part of the last decade, the Tunisian photographer has dedicated himself to taking portraits of foes, especially those captive to entrenched conflicts, born with the hatred of the other, such as the Israeli-Palestinian hostilities or the India-Kashmir rift. Ben Khelifa sees it as a way to make the viewer – and, hopefully, bitter rivals – see the human being behind the fighter.

“Fundamentally, as journalists, we’ve always been trying to arouse empathy so that viewers will care for a situation happening miles from their home or to others,” he says. “When I began as a photographer, I wanted to work for the most renowned magazines in order to reach the largest audience and touch the most souls. With time, I grew increasingly frustrated with the lack of results.”

It turned out that three images in a newspaper spread were not enough to bring on change. Nor were a dozen shared online. Nor even fifty or sixty bound in a book or displayed as a show. “The challenge is to devise mechanisms that will grab and hold people’s attention long enough for you to tell a complex story,” he says, two years after he had his first virtual reality experience when he joined the MIT’s Open Documentary Lab.

Virtual reality, with its potential to offer a fully engrossing experience, might just be the way, he believes, though it’s not without obstacles. Producing such an elaborate project is exorbitantly costly and requires a wide set of skills. Over 45 people have worked on The Enemy – some of whom were dedicated to rendering exclusively and with utmost accuracy skin, hair or the slightest movement.

“It is essential to make the presence of the combatant feel as genuine as possible,” says Ben Khelifa. “By reacting to the viewer’s behavior, the hologram is acknowledging his presence, which in turn, creates a cognitive reaction of reciprocity. The hologram appears more real.” So much so, that though participants could walk through the simulated fighter, none of them has done so. During a demonstration in Paris, one woman fled when the combatants appeared, unsure of whether they were going to come after her, and another turned away from Abu Khaled. She wanted to hear what he had to say, but staring the masked man in the eyes made her uneasy.

Since starting the project two years ago and basing himself on the reactions of his users, Ben Khelifa has been tweaking and fine tuning the experience, keeping it as simple and intuitive as possible. “The difficulty is that I can’t fully control how everything unfolds,” he says. “Some of it is in the hand of the user who needs to feel some agency. There’s a fine balance that needs to be achieved between directing the viewer and giving him freedom. I could add an endless amount of sensorial experiences, but that could quickly become overwhelming.”

The prototype for The Enemy is currently on view at the Tribeca Film Festival as part of the Storyscapes programming alongside other interactive experiences. Ben Khelifa hopes that within the next 20 months he will be able to add seven more duos of fighters that will interact with the viewers in different manners. He will also spend that time devising ways to make it more accessible, creating a traveling installation that could welcome more than one person at a time as well as an app version to be experienced at home.

And, he has plans to record with more accuracy the reactions of participants, monitoring their heart rate, keeping track of how close or distant to each combatant they get and noting how attentive they are. “Analyzing people’s responses will give us insights that can help us become more effective storytellers,” he says.